To the holiday-cheerful,

Today’s post comes to you from a very special guest, someone who can speak with far more authority about Easter than I ever could (and far more irony than I would ever dare), Mollie Wilson O’Reilly. Mollie is an associate editor of Commonweal Magazine, and blogs at Restricted View. You may have also caught her writing in The Village Voice, Nextbook.org, and Television Without Pity.

“The child of today will probably remember Easter as a sort of minor Christmas,” proclaimed this Life magazine article from 1939. “Easter today is second to Christmas as toy-buying time.”

Growing up a Catholic kid in the 1980s, I was reminded by my teachers every year that Easter is really the most important Christian holiday. Kids need to be told this because, in terms of secular hoopla (and toy-buying), Easter is a “minor Christmas” at best. For religiously motivated joy, you can’t beat it, but the consumer side of Eastertide never quite took off.

Growing up a Catholic kid in the 1980s, I was reminded by my teachers every year that Easter is really the most important Christian holiday. Kids need to be told this because, in terms of secular hoopla (and toy-buying), Easter is a “minor Christmas” at best. For religiously motivated joy, you can’t beat it, but the consumer side of Eastertide never quite took off.

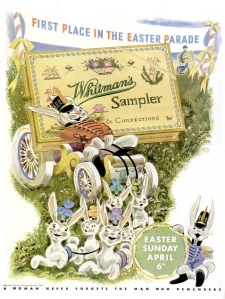

The failure to make a second Xmas out of Easter was not for lack of trying, as a perusal of Google’s online archive of midcentury Life magazines will show. Easter-themed advertising pops up every spring. Clothing gets a big push—gotta look good for that parade!—as do Whitman’s chocolates (right: “A woman never forgets the man who remembers”) and seasonal foods like Armour ham. (Or just ham in general.)

Then there are the less obvious seasonal tie-ins, like this ad for—well, see how long it takes you to figure it out: “Bright Easter finery. A smart Easter hat. Gay Easter flowers. It’s every woman’s right to glow with pride in the Easter parade. And, it’s no woman’s wish to go home and spend the rest of the day in the kitchen. There’s a hint for husbands here. Take the family out for dinner—where they have Wurlitzer music.”

Phonographs! Of course.

The 1939 article about the thriving Easter toy market referred to “bunnies that have grown to monstrous sizes” as a particularly popular treat. I think that phrasing really gets to the heart of what’s wrong with the commercial side of Easter in our culture: the total failure of imagination that is the Easter Bunny. Our Santa Claus legend is pretty solid: We know what he looks like, where he lives, what he does. But when it comes to the Easter Bunny, all we really know is that he’s an overgrown rabbit who delivers eggs and/or candy. But where does he come from? Where does he get the eggs? What, if anything, does he wear? And isn’t the whole idea sort of, well, frightening?

In 1939, as far as Life was concerned, the Easter Bunny was a Continental oddity. “In Europe, the hare is considered a sort of St. Nick who comes at night to leave colored eggs for good children,” the article above explains. But by 1947, E.B. is on the scene in America—and judging from this ad for Listerine toothpaste, he may or may not have genie-like powers: “If the Easter bunny could grant one wish, about your child’s appearance, you’d be wise to choose a friendly, radiant smile! However, if you don’t believe in the Easter bunny, and do believe in Oral Hygiene…”

A Life photographer caught these brothers (left) confronting the Bunny in Los Angeles in 1947: “To startled, half-frightened Christopher, older brother Peter explained the Easter legend. Enormous bunnies like this mysteriously appear every Easter, leave brightly colored eggs in hidden places and, just as mysteriously, disappear.” That is certainly not *the* Easter legend, but I’m not even sure it counts as *an* Easter legend. Are there really multiple Easter Bunnies?

Along with widespread uncertainty about what, exactly, the E.B. does, there is our collective failure to figure out what he should look like. In the meantime, we keep scaring children with giant rabbit costumes—a tradition that dates back at least to the 1950s, as you can see in photos from the University of Southern California’s digital library. This one below, from the 1958 Beverly Hills Easter Parade, is captioned “nineteen-months-old Mary Lee Anderson…cries as she is surrounded by three Easter Bunnies who jumped off float to greet little girls.” Can you blame her?

Pamela Schmidt, the “Easter Seal Sweetheart” of 1958 (below) held up much better when she came face to face with the Easter Bunny and the March Hare (I wonder if she could tell which was which?), while these little Los Angelenos, ca. 1951, look happy to be posing with their baskets, and no bunnies in sight.

Nobody sends Easter cards anymore, but considering the kinds of cards people used to send, that may not be such a bad thing. The University of Louisville’s Newton Owen Postcard collection has a large collection of Easter greetings from the earlier decades of the twentieth century, most featuring anthropomorphized animals that have grown to monstrous sizes. And what could be more monstrous than “two chickens in human clothing”?

Sometimes the chickens are beasts of burden, as in this image, captioned “woman in a chariot drawn by three very large chicks.” (Or perhaps it’s just an abnormally small woman?)

Many of these images have military overtones, perhaps in relation to the Great War. In some, uniformed rabbit soldiers bring you Easter wishes, astride their sturdy chickens:

But at other times the rabbits are the beasts of burden, and the chicks their masters:

Whimsy may be the intent, but I find these illustrations slightly nightmarish. And none gives me the willies more than this “Loving Easter Greeting,” which depicts a chick roasting eggs over a stove. Is this proof that “Suicide Food” is not a recent phenomenon? Please note that the person who sent this card back in 1911 scrawled “This is I” across the apron of the cannibal chick. Loving Easter Greetings indeed!

Yours in waiting for the Easter Bunny,

Mollie

What digital resources do you rely on, or would you recommend?

What digital resources do you rely on, or would you recommend?

Today, I’ll head south of Massachusetts to Pennsylvania. I’ve been there only a few times in my life—once to Philadelphia, once to Pittsburgh, once to Sesame Place (I was four!), and once to Scranton for a wedding (plus the thrill of The Office connection).

Today, I’ll head south of Massachusetts to Pennsylvania. I’ve been there only a few times in my life—once to Philadelphia, once to Pittsburgh, once to Sesame Place (I was four!), and once to Scranton for a wedding (plus the thrill of The Office connection).