To the relaxation-inclined,

Like many people, my first exposure to theater came not from any Broadway house but the humbler stages of our local high school. Trust me, you haven’t seen Fiddler on the Roof until you’ve seen my brother in his walk-on-role as a priest! Or Twelve Angry Men performed by twelve not angry so much as angsty boys—in the round!

I’m happy to say, my theatrical horizons have expanded considerably since then, from the mainstream to the avant-garde, Broadway to the Edinburgh Fringe. And while we can rarely go back and see a live performance once it’s over, thanks to the digital archive, we can see what the actors wore, and what their sets looked like.

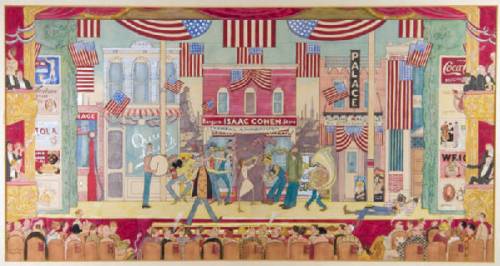

Mordecai Gorelik, for one, designed sets for the famed Group Theatre, and eventually Hollywood. Over at the CARLI Digital Collections, you can view many of his drawings, including this one from the 1925 modernist play Processional.  Take a look, too, at Miami University’s Randy Barceló Collection, featuring drawings by the Cuban-born costume designer behind Jesus Christ Superstar, and many lesser known productions. Below are two costumes he created for a 1994 ballet ¡Si Señor! ¡Es Mi Son!, produced by New York’s Ballet Hispanico. I’d like to see the folks on Project Runway attempt these.

Take a look, too, at Miami University’s Randy Barceló Collection, featuring drawings by the Cuban-born costume designer behind Jesus Christ Superstar, and many lesser known productions. Below are two costumes he created for a 1994 ballet ¡Si Señor! ¡Es Mi Son!, produced by New York’s Ballet Hispanico. I’d like to see the folks on Project Runway attempt these.

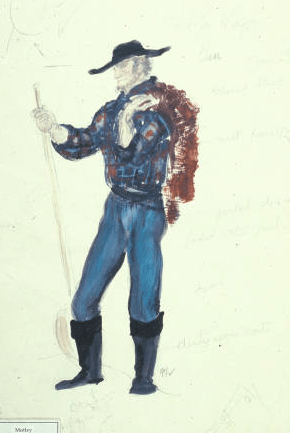

Last but not least, the Motley Collection from U. of Illinois includes many costume and set designs from New York theater, throughout the twentieth century. The image on the left comes from a production of Romeo and Juliet, on the right from Paint Your Wagon.

Sartorially yours,

Stephen

And be sure to head over to the again bounteous

And be sure to head over to the again bounteous

Today, I’ll head south of Massachusetts to Pennsylvania. I’ve been there only a few times in my life—once to Philadelphia, once to Pittsburgh, once to Sesame Place (I was four!), and once to Scranton for a wedding (plus the thrill of The Office connection).

Today, I’ll head south of Massachusetts to Pennsylvania. I’ve been there only a few times in my life—once to Philadelphia, once to Pittsburgh, once to Sesame Place (I was four!), and once to Scranton for a wedding (plus the thrill of The Office connection).

The nominations are in! No, not for the Oscars or the Golden Globes, but the awards we’ve all been waiting for: The

The nominations are in! No, not for the Oscars or the Golden Globes, but the awards we’ve all been waiting for: The  The search for meaningful spiritual connection is, of course, nothing new among American Jews. Just take a case in point from the late nineteenth century (how do you like that segue?!): the

The search for meaningful spiritual connection is, of course, nothing new among American Jews. Just take a case in point from the late nineteenth century (how do you like that segue?!): the